Meanwhile, Lucy and Genevra hang out with each other quite often. Genevra, who has by now shown herself to be a hopeless flirt, repeatedly mentions a certain "Isidore" - an unfortunate young man who has developed an ardent affection for her. It's the typical infatuated/duped-guy-willing-to-jump-off-cliff-for-flighty-girl situation. I always find those to be among the top 5 most annoying situations in a book. JUST GET OVER HER, FOOL. Ah, I feel better now.

At the back of the garden behind the school is a tree-lined alley, which has become a favorite haunt of Lucy's. While sitting there one day, a box mysteriously drops from the window of a house nearby. Inside is a bouquet of flowers and a sappy love note. Out of the blue, Dr. John appears on the scene, intent on recovering the box and its contents. Suddenly they spot Madame Beck characteristically approaching, presumably to investigate the commotion. Dr. John disappears. Madame Beck acts suspiciously.

I found what happens next to be rather funny - Madame Beck (after searching Lucy's things again) leaves the house in an obvious fashion, and Dr. John comes for a visit. He and Lucy end up alone in a room and talk about the box, and he reveals that, although he didn't write the note, he knows who did and for whom it was intended. He's about to tell when the door suddenly makes a noise which is followed by a sneeze, and Madame Beck cooly walks through the room. The poor woman is found out in spite of her tricks.

The end of the school year comes and the school puts on a ball. During the festivities, the questions of what was going on with Madame Beck & the young Dr. John, and the identities of the two apparent lovers are resolved -

- Madame Beck had a crush on Dr. John.

- Dr. John turns out to be Isidore.

- The box/love note were from a rival - an empty-headed pretty boy. Lucy tries to show him that Genevra isn't exactly a fine catch, but he tells her she's being too severe. I like how she sets him straight -

HAHA.“I love Miss Fanshawe far more than De Hamal [the rival] loves any human being, and would care for and guard her better than he. Respecting De Hamal, I fear she is under an illusion. The man’s character is known to me, all his antecedents, all his scrapes. He is not worthy of your beautiful young friend.”

“My ‘beautiful young friend’ ought to know that, and to know or feel who is worthy of her,” said I. “If her beauty or her brains will not serve her so far, she merits the sharp lesson of experience.”

“Are you not a little severe?”

“I am excessively severe—more severe than I choose to show you. You should hear the strictures with which I favour my ‘beautiful young friend,’ only that you would be unutterably shocked at my want of tender considerateness for her delicate nature.”

“She is so lovely, one cannot but be loving towards her. You—every woman older than herself must feel for such a simple, innocent, girlish fairy a sort of motherly or elder-sisterly fondness. Graceful angel! Does not your heart yearn towards her when she pours into your ear her pure, childlike confidences? How you are privileged!” And he sighed.

“I cut short these confidences somewhat abruptly now and then,” said I. “But excuse me, Dr. John; may I change the theme for one instant? What a godlike person is that De Hamal! What a nose on his face—perfect! Model one in putty or clay, you could not make a better or straighter or neater; and then, such classic lips and chin; and his bearing—sublime.”

“De Hamal is an unutterable puppy, besides being a very white-livered hero.”

“You, Dr. John, and every man of a less refined mould than he, must feel for him a sort of admiring affection, such as Mars and the coarser deities may be supposed to have borne the young, graceful Apollo.”

“An unprincipled, gambling little jackanapes!” said Dr. John curtly, “whom, with one hand, I could lift up by the waistband any day, and lay low in the kennel if I liked.”

“The sweet seraph!” said I. “What a cruel idea! Are you not a little severe, Dr. John?”

Anyways, school ends and as Lucy has nowhere to go, she stays in Villette. The utter loneliness of the situation depresses her, and she develops a fever. She wanders around town and ends up in a confessional, spilling everything out to a priest, who asks her to see him the next day. I was so scared while reading that she'd do it, but to my relief, Lucy stands him up and does not become a papist. Ah.

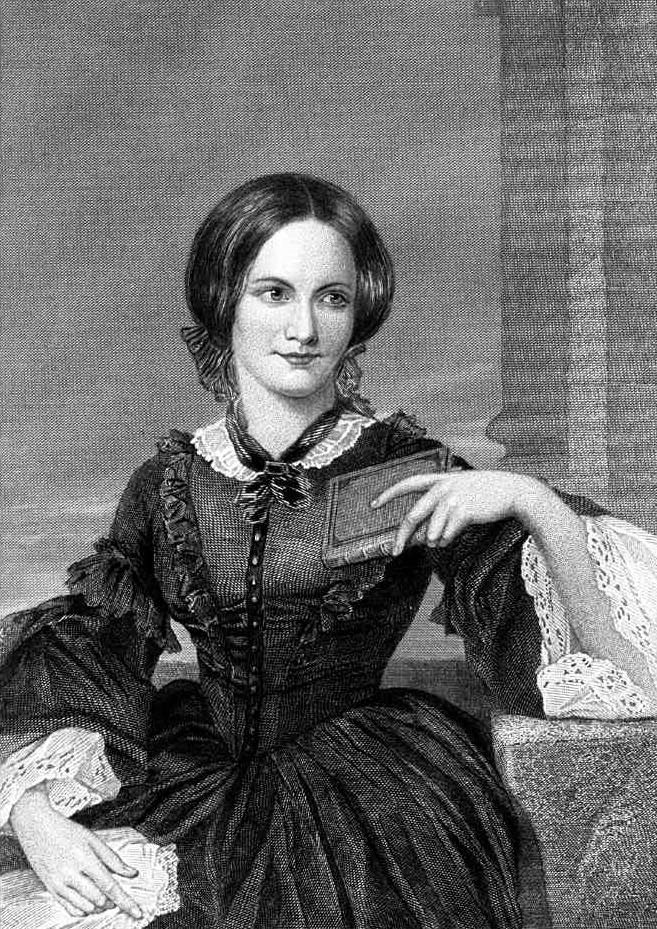

I really like Lucy. She's sensible, philosophical, analytical, curious, and has a travel bug. She slightly reminds me of Jane Eyre. Interesting how Charlotte Bronte uses a similar type of heroine in her novels. I wonder if it's the same in Shirley and The Professor? I heard that Jane Eyre was slightly auto-biographical. I heard the same of Villette. And The Professor. Perhaps she wrote the books with herself in mind as the heroine, sort of getting to imagine what her life could have been like in different situations? That'd be an interesting thing to keep in mind as I keep reading.

Wow, this got long.