Thursday, March 11, 2021

On the humanities

Sunday, January 17, 2021

40 pages and worth every one of them

This I do so that, in comparing your sorrows with mine, you may discover that yours are in truth nought, or at the most but of small account, and so shall you come to bear them more easily.

No one, methinks, could fail to understand how persistently that undisciplined body of monks, the direction of which I had thus undertaken, tortured my heart day and night, or how constantly I was compelled to think of the danger alike to my body and to my soul. I held it for certain that if I should try to force them to live according to the principles they had themselves professed, I should not survive.

Those Mondays are just killers.

Friday, November 13, 2020

Calm and uproar

|

| Wisconsin |

“I’m not leaving for anywhere, am I?” says the Word of God. Imbed your home in him, place in safekeeping with him whatever you have from him, my soul—if only because you’re worn out by lies. Place in safekeeping with the truth whatever you possess from the truth, and you won’t lose anything. The things that have rotted in you will flower again, and all the afflictions that make you sluggish will be healed, and the things that are slack will be remade and renewed and hold together with you. They won’t drop you in the depths (where they themselves go), but will stand steady at your side and hold their ground in the presence of God, who also stands steady and holds his ground.

(St. Augustine, Confessions 4.16; Sarah Ruden, trans.)

Lately, I've been reading Sarah Ruden's translation of Augustine's Confessions, and it's made the book come alive in a way it never had for me before. The prose is beautiful, making Augustine's thoughts vivid, memorable, and - inevitably for 2020 - deeply cathartic. It's been an absolute pleasure to slowly take in, like reading a high-quality, meditative, contemporary novel (meant in the best possible sense).

In my current mental space, it's impossible to separate the excerpt above from two previous literary moments in my life (Milton in college and T.S. Eliot in grad school). All three of these speak to one of the dialogues in the western tradition that I find most poignant: specifically, the interplay between identifying/pursuing the good life and coping with devastating loss. Especially during the past few years, I've been growing to appreciate how, for an overwhelming number of the authors in our tradition, the two are more closely linked than you'd initially believe them to be.

There is so little permanence in our lives, and it's something I think the world has been collectively experiencing in a profound way for the majority of this past year. Transience and wandering are recurring themes in the Confessions, and I love how Augustine touches on a paradox initially hinted at by Christ ("For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it; but whoever loses his life for My sake will find it," Matt. 16.25). By handing the promises God gives us back to Him for "safekeeping," we can be certain they will always be ours. We'll never lose the most important things in life.

Significantly, Augustine assumes that we develop this ethos by engaging with the written word. He identifies God's promises as truth, and truth can be found in Scripture. Immersion in objective truth is the best antidote to despair. (Sidebar: this doesn't necessarily involve going on some painfully-subjective pietist safari of color-coded bible study. I was recently shocked to discover that high-functioning low achievers like me can read the whole thing in a year if you do about 3 chapters a day. That's like 5-10 minutes of reading.)

I've had my share of disturbingly dark moments in recent years, but I'm starting to recognize the hand of God even in the "rock bottom" experiences, because they showed me how much I need Him. As Augustine says just a few sentences earlier, "the Word itself shouts for you to return, and there lies a place of calm that will never know any uproar, where love is not abandoned unless it abandons."

Sunday, September 13, 2020

Sunday night Donne

Wilt thou love God as he thee? then digest,

My soul, this wholesome meditation,

How God the Spirit, by angels waited on

In heaven, doth make His temple in thy breast.

The Father having begot a Son most blest,

And still begetting—for he ne'er begun—

Hath deign'd to choose thee by adoption,

Co-heir to His glory, and Sabbath' endless rest.

And as a robb'd man, which by search doth find

His stolen stuff sold, must lose or buy it again,

The Sun of glory came down, and was slain,

Us whom He had made, and Satan stole, to unbind.

'Twas much, that man was made like God before,

But, that God should be made like man, much more.

(Holy Sonnet 15)

Having never read all of Donne's Holy Sonnets before (and they gave me English degrees!), I fell in love with his writing even more when I read this tonight. Apparently producing some of the most seminal, beautiful poetry in the English language just isn't enough if you don't casually throw it together by framing it in systematic trinitarian theology. In 14 lines he covers:

- Creation

- Theology proper (+ emphasizing orthodox distinctions)

- Anthropology

- Biblical covenantal typology

- The fall

- The incarnation

- Christ's exaltation and humiliation

- The atonement

- Double imputation

- Predestination

- Adoption

- Indwelling of the Holy Spirit

- Eschatology.

Sunday, June 28, 2020

More two kingdoms

Finally, the Christian’s attitude should be charitable, compassionate, and cheerful. If Christians are truly confident in God, as just discussed, they must show charity to their neighbors, for faith works through love (Gal 5:6). They should overflow with the compassion of their Lord (e.g., Col 3:12; cf. Matt 9:36, e.g.). Christians are often quick to view people of different political opinion as their enemies. In some cases, they may indeed be enemies, yet love for enemy is a chief attribute of Christ’s disciples (Matt 5:43–48). It is deeply unbecoming when Christians complain incessantly about the state of political affairs, especially Christians who enjoy levels of prosperity, freedom, and peace that are the envy of the world. It is easy to be angry about losing one’s country—as if any country ever belonged to Christians. It is easy to demonize political opponents—as if Christians themselves are not sinners saved entirely by grace. It is easy to become bitter—as if “the lines” had not “fallen for [them] in pleasant places,” as if they did not have “a beautiful inheritance” (Ps 16:6). Christians have become heirs of a kingdom that cannot be shaken, and thus they say, “My heart is glad, and my whole being rejoices” (Ps 16:9). Those who are heirs of new creation are truly the most blessed of people, and while they wait for their Lord’s return they have opportunity to love and bless all of their neighbors, even those who do not respond in kind, and to do so with a joyful spirit.

(Politics After Christendom, pp. 168-169)

Sunday, June 14, 2020

Law and memory

Every priest stands daily ministering and offering time after time the same sacrifices, which can never take away sins; but He, having offered one sacrifice for sins for all time, sat down at the right hand of God, waiting from that time onward until His enemies be made a footstool for His feet. For by one offering He has perfected for all time those who are sanctified. And the Holy Spirit also testifies to us; for after saying,

“This is the covenant that I will make with them

After those days, says the Lord:

I will put My laws upon their heart,

And on their mind I will write them,”

He then says,

“And their sins and their lawless deeds

I will remember no more.”

(Hebrews 10.11-17)

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Staying alive

After Abraham had rested for a few days, Jehannot asked him what sort of opinion he had formed about the Holy Father and the cardinals and the other members of the papal court. Whereupon the Jew promptly replied:

'A bad one, and may God deal harshly with the whole lot of them. And my reason for telling you so is that, unless I formed the wrong impression, nobody there who was connected with the Church seemed to me to display the slightest sign of holiness, piety, charity, moral rectitude or any other virtue. On the contrary, it seemed to me that they were all so steeped in lust, greed, avarice, fraud, envy, pride, and other like sins and worse (if indeed that is possible), that I regard the place as a hotbed for diabolical rather than devotional activities. As far as I can judge, it seems to me that your pontiff, and all of the others too, are doing their level best to reduce the Christian religion to nought and drive it from the face of the earth, whereas they are the very people who should be its foundation and support.

'But since it is evident to me that their attempts are unavailing, and that your religion continues to grow in popularity, and become more splendid and illustrious, I can only conclude that, being a more holy and genuine religion than any of the others, it deservedly has the Holy Ghost as its foundation and support. So whereas earlier I stood firm and unyielding against your entreaties and refused to turn Christian, I now tell you quite plainly that nothing in the world could prevent me from becoming a Christian. Let us therefore go to the church where, in accordance with the traditional rite of your holy faith, you shall have me baptized.'

(Boccaccio, Decameron, pp. 40-41)

Monday, October 28, 2019

Keach and poetics (pt. 3)

|

| Hohenschwangau, Bavaria |

2. Christ is the Spring, or the Original

Of earthly beauty, and Celestial.

That beauty which in glorious Angels shine,

Or is in Creatures natural, or Divine,

It flows from him: O it is he doth grace

The mind with glorious beauty, as the face.

(The Glorious Lover, II.iii.49-54)

“...if thou believest that God is beauty and perfection itself, why dost not thou make him alone the chief end of all thine affections and desires? for if thou lovest beauty, he is most fair; if thou desirest riches, he is most wealthy; if thou seekest wisdom, he is most wise. Whatsoever excellency thou hast seen in any creature, it is nothing but a sparkle of that which is in infinite perfection in God...”Keach also emphasizes way God's beauty is the origin or source of beauty as we experience it. Its function as a fountainhead for created beauty establishes its authority over the latter, as well as showcasing its role as the source which creates and empowers it. Because of this relationship, earthly beauty, at its best, is characterized by its humility. It is not something that is meant to draw attention to itself, but rather to draw the beholder's attention back to its divine origins. Yet, at the same time, this relationship also elevates earthly experiences of beauty because of their ability to connect humanity with the numinous.

I think it's also important to note that while the philosophical undertones are an interesting possibility here, it's likely that Keach is primarily focused on emphasizing orthodox trinitarian concepts like God's aseity and simplicity, and the way we bear his image in His communicable attributes. Not only is He the font from which we receive our experience of beauty or even beauty in its perfection, He is beauty. There's a sense that this portion of The Glorious Lover synthesizes New Testament discussions of God's ontology with the bride's joy in the beauty of her beloved in the Song of Solomon:

“For from Him and through Him and to Him are all things. To Him be the glory forever.” (Romans 11.36)

“The God who made the world and all things in it, since He is Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in temples made with hands; nor is He served by human hands, as though He needed anything, since He Himself gives to all people life and breath and all things; and He made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined their appointed times and the boundaries of their habitation, that they would seek God, if perhaps they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us; for in Him we live and move and exist, as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we also are His children.’ Being then the children of God, we ought not to think that the Divine Nature is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and thought of man.” (Acts 17.24-28a)

“My beloved is dazzling and ruddy,

Outstanding among ten thousand.

...And he is wholly desirable.

This is my beloved and this is my friend,

O daughters of Jerusalem.” (Song of Solomon 5.10, 16)

Keach concludes the passage with an interesting distinction between beauty of the “mind” and beauty of the “face.” On one level, this can be understood as a comparison between inner and outer beauty. In Sonnet XV of his Amoretti cycle, Spenser devotes the first twelve lines of his poem cataloguing his beloved's appealing physical traits, but, in the turn, he declares that her most important/precious feature is her character:

“But that which fairest is, but few behold,However, it's crucial to recognize that this is not simply a distinction between internal and external qualities (I'm staring at you, Every Contemporary Beauty Movement), but more precisely, a focus on the relationship between beauty and intellect. In the Renaissance context, beauty was not valued only for carnal/physical considerations, but, more importantly, for its intellectual qualities. To view it as a merely material phenomenon was to debase it to an animalistic drive and turn it into lust. This is where we get all the epithets about “brutish” appetites. Beauty was pure and true when it engaged all aspects of being human; in this context, it elevated the individual. Thus we see in Shakespeare's (most?) famous sonnet language that glorifies the enduring nature of an intellectual love connection over the vanishing appeal of the senses:

her mind adornd with vertues manifold.”

All in all, it's an emphasis on conceptual beauty, or, in other words, virtue gained through understanding. For Keach, this ties back to the reformed dogma that faith and knowledge necessarily go hand in hand. Hearing the Word brings about faith (i.e. the ability to see Christ's beauty), and once we have this faith, we can finally begin to know Him.“Let me not to the marriage of true mindsAdmit impediments. Love is not loveWhich alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

...Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle's compass come...” (CXVI)

Finally, I find it interesting that Keach doesn't mitigate material/earthly beauty here, but rather, affirms it. The key is that it must always be tied to virtue. And so we circle back to the ubiquitous Renaissance understanding of aesthetics, of art as something intended to “delight and instruct” (Sidney). I think that we can see this as yet another instance of Keach's project of reinventing the romance genre into something fundamentally wholesome - a marriage of aesthetics and devotion.

Tuesday, July 2, 2019

Keach and poetics (pt. 2)

|

| Hofgarten, Munich |

1. His Beauty is so much desirable,

No souls that see it any ways are able

For to withstand the influ’nce of the same;

They’re so enamour’d with it, they proclaim

There’s none like him in Earth, nor Heav’n above;

It draws their hearts, and makes them fall in love

Immediately, so that they cannot stay

From following him one minute of a day.

The flock is left, the Herd, and fishing Net,

As soon as e’er the Soul its Eye doth set

Upon his face, or of it takes a view,

They’ll cleave to him, whatever doth insue.

(The Glorious Lover, II.iii.37-48)

"The love of God does not find, but creates, that which is pleasing to it. The love of man comes into being through that which is pleasing to it."

Whom have I in heaven but you?Just a glimpse of Christ is enough for the Christian to leave behind all secular concerns and gaze on Him - a gaze so strong that Keach considers it a kind of "cleaving." This focus on Christ effectively blinds the Christian to the doubts and material threats that accompany a relationship with God, because the Christian's eyes are "enamoured" with the greater spiritual reality now visible to her.

And there is nothing on earth that I desire besides you.

My flesh and my heart may fail,

but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever. (vv. 25-26)

Keach's use of the word "enamour" here is interesting, given the Renaissance literary background The Glorious Lover emerges from in England. Spenser, Sidney, and Shakespeare often connect the experience of being in love with sickness and sorcery (the connection between the latter two would be familiar to readers because of the Greek term, "pharmakeia"). When Titania recovers from her love potion in A Midsummer Night's Dream, she exclaims:

My Oberon, what visions have I seen!To be "enamoured" was an inherently visual experience, as Shakespeare's Titania conceives of her love as a type of vision. Similarly, in his old Arcadia, Sidney utilizes the term in conjunction with the devious acts of Cupid (who is known for his arrows that, when striking someone, cause the victim to fall in love with the first person they see):

Methought I was enamored of an ass. (IV.i.77-78)

But whom to send for their search she knew not, when Cupid (I think for some greater mischief) offered this Plangus unto her, who from the day of her first imprisonment was so extremely enamoured of her that he had sought all means how to deliver her. (54)Thus, to be enamoured is to be enchanted. Though he dispenses with the sinister undertones of the term present in mainstream literature, Keach remains very interested in its magical connotations. The Calvinism undergirding Keach's theology underscores the supernatural nature of conversion, and the notes of magic in his language reinforce both the spirituality as well as powerful intervention in natural affairs that is taking place.

Keach is not the first devotional poet to be drawn to the spiritual sight/blindness motif. There's a parallel moment in The Temple, in which Herbert frames conversion in language of sight and restoration:

Our eies shall see thee, which before saw dust;It isn't surprising that Keach is drawn to the sight motif in order to carry his point, given his extensive work on Scriptural metaphors and the prevalence of the trope in biblical literature. In Tropologia, Keach's introduction to the segment of metaphors pertaining to the word of God includes a lengthy discussion of light and sight. He writes:

Dust blown by wit, till that they both were blinde:

Thou shalt recover all thy goods in kinde,

Who wert disseized by usurping lust:

All knees shall bow to thee; all wits shall rise,

And praise him who did make and mend our eies. ("Love II")

As light is Glorious because it is the most Excellent Rayes, Resplendency and Shinings forth of the Sun; so is the Gospel, because 'tis the glorious shining forth and resplendency of Jesus Christ the Sun of Righteousness.The light of the Gospel - contained in the words of Scripture - awakens faith in the sinner, enabling her eyes to see the glory and beauty of Christ.

The overall tone of this passage is one of the spiritual transcending, intervening in, or overriding the carnal. The supernatural nature of the Gospel miraculously restores spiritual sight to blind eyes while simultaneously blinding them to the distractions of the world. Conceptions of beauty and ugliness become fluid in the accompanying reversal of values. This primacy of the spiritual echoes Keach's apology for his work, in which he condemns worldly versions of the romance genre and reinvents these forms for his spiritual task:

How many do their precious time abuseSpiritually-enlightened poetry, which demonstrates the desirability of Christ by highlighting His beauty, redeems the romance genre from its corrupt uses in the secular realm. Enlightenment is a key theme in Keach's poetry, something he reinforces by baptizing the very genre itself.

On cursed products of a wanton Muse;

On trifling Fables, and Romances vain,

The poisoned froth of some infected Brain? (43-46)

Here’s no such danger, but all pure and chast;

A Love most fit by Saints to be embrac’d:

A Love ‘bove that of Women... (51-53)

[Part One]

Monday, May 27, 2019

Comedy and the Psalms

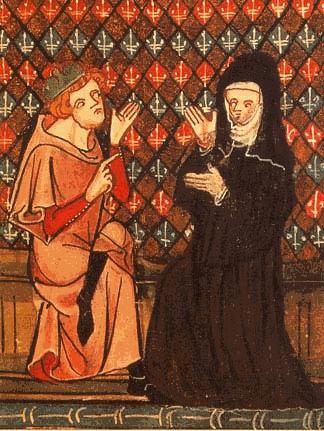

| "The Kiss of Peace and Justice," Laurent de La Hyre |

Praise the Lord!

Praise, O servants of the Lord,

Praise the name of the Lord.

Blessed be the name of the Lord

From this time forth and forever.

From the rising of the sun to its setting

The name of the Lord is to be praised.

The Lord is high above all nations;

His glory is above the heavens.

Who is like the Lord our God,

Who is enthroned on high,

Who humbles Himself to behold

The things that are in heaven and in the earth?

He raises the poor from the dust

And lifts the needy from the ash heap,

To make them sit with princes,

With the princes of His people.

He makes the barren woman abide in the house

As a joyful mother of children.

Praise the Lord!

(Psalm 113)