Let’s talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs,

Make dust our paper, and with rainy eyes

Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth.

Let’s choose executors and talk of wills.

And yet not so, for what can we bequeath

Save our deposèd bodies to the ground?

Our lands, our lives, and all are Bolingbroke’s,

And nothing can we call our own but death

And that small model of the barren earth

Which serves as paste and cover to our bones.

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground

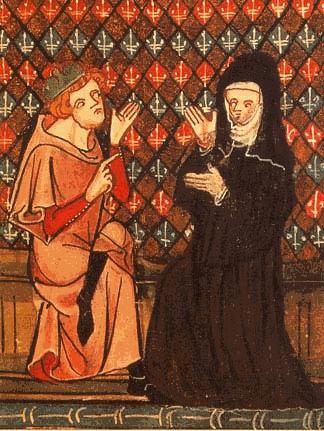

And tell sad stories of the death of kings—

How some have been deposed, some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed,

Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed,

All murdered. For within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps Death his court, and there the antic sits,

Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp,

Allowing him a breath, a little scene,

To monarchize, be feared, and kill with looks,

Infusing him with self and vain conceit,

As if this flesh which walls about our life

Were brass impregnable; and humored thus,

Comes at the last and with a little pin

Bores through his castle wall, and farewell, king!

Cover your heads, and mock not flesh and blood

With solemn reverence. Throw away respect,

Tradition, form, and ceremonious duty,

For you have but mistook me all this while.

I live with bread like you, feel want,

Taste grief, need friends. Subjected thus,

How can you say to me I am a king?

(Richard II III.ii.150-182)

I didn’t appreciate Richard II in quite the way that Shakespeare intended it until I encountered corruption myself. Richard II was a far cry from the ruthlessness of Richard III, but his weakness is just as reprehensible as the latter’s criminality. I am naturally cautious, and I have learned that timidity can wield just as much injustice as tyranny. Sin overturns kingdoms with disturbing rapidity.