Amid the reckless academic decisions I have made this semester (including applying to only one grad school.....the fallout from that is another post, though), I found myself taking six classes, plus unofficially "auditing" someone else's independent study. That's 21 credits. I was slightly terrified going into it, but SO FAR it hasn't been too bad. I just slavishly keep on top of my homework every night. (In an ironic twist of fate, my completely neurotic fixation on homework this semester has made me the most productive I have yet been, and I actually have more free time* than I did before.)

All of this is a really long-winded lead-up to the subject of this post - the aforesaid independent study audit. Another irony, despite being the class I didn't need to worry about, it was actually the one that made me the most nervous, because of the subject matter: Postmodern Semiotics.

Now, here, if you're like me, you're wondering: WHAT THE HECK IS POSTMODERN SEMIOTICS?

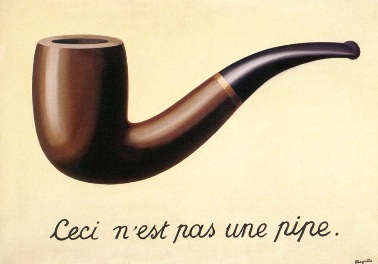

Semiotics is the study of how we assign things meaning and the relationship between symbols and the ideas they represent. A "famous" example of the idea behind contemporary semiotics is the painting by Rene Magritte called "The Treachery of Images":

|

| Translation: "I am not a pipe" |

Magritte is making both a joke and a statement on semiotics. The painting depicts a pipe, but the image we see isn't actually a pipe. It's only a picture of one. Ferdinand Saussure, one of the founders of modern semiotics, made a distinction between the "signifier" (in this case, the picture/painting) and the "signified" (the concept of a pipe itself). The strong Postmodernism comes in when Saussure claims that the connection between these two concepts is largely arbitrary. In language, this plays out in the way that not all words in one language directly correspond to similar words in another. One of my friends is a German major, so most of the examples I'm aware of are between English-German: We don't have a word for "schadenfreude" (pleasure in another person's pain), and apparently German has no equivalent for "creepy." Saussure and his followers would argue that different languages contain different ideas; we create words and assign meanings to them.

I had no idea what most of this was until several weeks ago, but, thanks to the classical education I was given (shameless plug), I was able to recognize that this conversation about semiotics is not new at all. In fact, the very "postmodern" approach to the connection between words and ideas simply goes back to the Medieval debates over Nominalism and Realism.

- Realism affirms Plato's theory of universals and particulars. To go back to the Magritte painting, Realists would say that every concept exists in two ways: The overarching, universal idea (pipe-ness), and each particular time it is represented in daily life (all the various pipes in the world, though different, are still tied together by their conformity to "pipe-ness"). We call a pipe a "pipe" because it embodies the idea of "pipe-ness."

- Nominalism rejects the existence of universals. We don't have any abstract ideals of "pipe-ness"; we just have pipes. We call a pipe a "pipe" because that is simply what we want to call it. In other words, when we create the word "pipe" we are also creating the concept of a "pipe." There may exist similarities between one pipe and another - and that's why they share the same name - but overall, they are their own entities. From what I understand, Saussure &co. would be more closely aligned with this view, because both emphasize the arbitrariness of language/signs.

I have always been sympathetic to Platonism, and really can't get on board with Nominalism's outright rejection of universal concepts. I find a lot to agree with in Augustine, who argued that the ideas we experience in life - love, for example - flow from the mind and attributes of God.

And now, I finally make it to the point of my post: Today, I was reading the creation narrative in Genesis 1-2. It struck me that God first created things, and then named them. In other words, ideas/objects preceded words. I've spent all morning thinking about this and I still haven't arrived at a satisfying conclusion. Would this be an argument for or against Nominalism? At first, I thought it was clearly implying a more Realist approach, because it would seem to say that "lightness" preceded the word "light." But perhaps the fact that Adam was given the task of naming the creatures would suggest that he was given the opportunity to assign differences between the species. I'm still leaning toward the former, but I would be really interested in hearing arguments from both sides.

Going to need to email my professor.

*Free time is a completely relative concept, and in this case means the homework ends with just enough time for a potential of 8 hours of sleep a night, assuming I do not (gasp) do some personal reading or go out with friends.