Love built a stately house; where Fortune came,And spinning phansies, she was heard to say,That her fine cobwebs did support the frame,Whereas they were supported by the same:But Wisdome quickly swept them all away.

Then Pleasure came, who, liking not the fashion,Began to make Balcones, Terraces,Till she had weakned all by alteration:But rev’rend laws, and many a proclamationReformed all at length with menaces.

Then enter’d Sinne, and with that Sycomore,Whose leaves first sheltred man from drought & dew,Working and winding slily evermore,The inward walls and sommers cleft and tore:But Grace shor’d these, and cut that as it grew.

Then Sinne combin’d with Death in a firm bandTo raze the building to the very floore:Which they effected, none could them withstand.But Love and Grace took Glorie by the hand,And built a braver Palace then before.

George Herbert - “The World”

Sunday, December 16, 2018

Goodnight

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Coming clean

|

| My dad’s parents - 1945 |

|

| My mom’s parents - 1952 |

|

| My parents - 1990 |

|

| Us - 2018 |

Two years ago today, I wrote this post. Less than 3 weeks later, this guy a friend of mine had been telling me about for a year sent me a friend request on Facebook. Over the next two years, one thing led to another, and in addition to picking up a graduate degree and new job, I thought, “why not add a husband to the mix as well?”

Back when I was in college, I decided that as long as I was unmarried, I’d stick around in school collecting degrees. In keeping with this sentiment, he waited until the day after I handed in my last paper to propose, choosing the gardens surrounding a transplanted medieval French chapel situated in the middle of my university as the scene of the crime. There were some serious Gaudy Night vibes. We got married on the day he - a year earlier - realized he wanted to marry me (September 28th). The English major in me is so proud of all this allusiveness.

I still stand by the spirit of everything I wrote in my post two years ago, although the Reformed Baptist landscape is radically different now. As a result, I suspect it is even more difficult to find a like-minded spouse. However, as someone who became an exception to her own forecast, I am thankful I didn’t compromise. You know you picked the right one when you come back from your honeymoon, which included visits to three schools, three bookstores, and three libraries, with a trunk-load of books. LIVING THE DREAM.

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Sacramental history

"We must be consumed either by the anger of the storm god or by the love of the living God. There is no way around life and its sufferings. Our only choice is will we be consumed by the fire of our own heedless fears and passions or allow God to refine us in his fire and to shape us into a fitting instrument for his revelation, as he did Moses. We need not fear God as we fear all other suffering, which burns and maims and kills. For God's fire, though it will perfect us, will not destroy, for 'the bush was not consumed.'

This insight into God is the unearthly illumination that will light up all the greatest works of subsequent Western literature. From the psalms of David and the prophecies of Isaiah to the visions of Dante and the dreams of Dostoevsky, the bush will burn but will not be consumed. As Allen Ginsberg will one day write, 'The only poetic tradition is the voice calling out of the burning bush.'"

Thomas Cahill, The Gifts of the Jews, 164.

I've been drawn to this quote for several years now. It brings to mind recurring themes of fortitude and hope that I never seem to stray very far from in my reading. Cahill's statements are reminiscent of Peter Leithart’s notion of “deep comedy,” which, in a literary context, is analogous to Shakespeare's genre of the tragicomedy. Although I’ve previously written on the reassuring nature of a “literary” reading of history, I hadn’t thought till now of this as also being an eminently sacramental practice as well (You can probably blame my recent medievalist joyride for this one).

A sacramentalist conception of history is one with a high view of providence.

A sacramentalist conception of history is one with a high view of providence.

A high, sacramental view of providence offers an alternative perspective to the conventional idea of history as a series of events carried out by us. We do not create history - it is something we receive. This is not to mitigate our role as agents in the plan of God’s providence. We receive, but we are not passive. When engaging in baptism or the Lord’s supper, we are active participants - there isn’t a supernatural tsunami of water that envelops us, nor are we force-fed the elements. However, even though we truly partake in the sacraments, the focus is not on our actions as such, but on what God does for us through them. It’s the same in history. To view it primarily as a transcript of human actions can only lead to despair; it is an endless, steadily-escalating spiral of self-destruction. However, if we consider it a record of God’s gracious intervention in this cycle, drawing our attention by types and shadows to a promised restoration, it is great cause for hope.

Not only does a sacramental view of history consider providence as something we receive, it is also an emphatic belief that we will be helped by what we experience in life. If the sacraments are not meant to be seen as things we do, they must be something more than mere memorials; rather, they are the means of grace by which God strengthens our faith. To see history sacramentally, we stand confident that God will use these events both for his glory and our benefit. It’s easy for me to assent to this claim when I can see the direct connection between what I’m going through and a positive trajectory in my spiritual life; when I’m encouraged by fellowship with other Christians or witness new converts join the church, I have no problem believing that I will benefit from what I see. It’s much more difficult to trust this when providence pushes me to rely on God’s promises. The times when God seems to be working against his revealed will, when a hopeful explanation for what is happening to me is impossible to recognize, when people go through apparently senseless suffering - these are the moments that force us to live in faith. We must look back in history, not only to times when good this came out of evil, but also to God’s promises that, though there might never be a satisfying explanation in this life, all will be made well in the one to come. It is both forward and backward thinking.

I find that in my life, viewing history sacramentally means that I must be stubbornly submissive to God’s will. Trusting him doesn’t always make sense, and it often feels more terrifying than comforting in the moment. It requires me to go against all of my fallen instincts. Sometimes the only thing keeping me going is stubbornness (which itself is a divine intervention in my life). But it is the only way we can view history as a deep comedy, as an experience in which God sacramentally draws us closer to himself. Suffering is an inevitability in a fallen world, and as Cahill writes, we can either entrust ourselves to God’s hand or else plunge ourselves deeper into destruction. Grace may be painful, but that is not a fault on the part of God; it is ours for distorting it in our perception. Gracious fire perfects rather than destroys.

Sunday, November 25, 2018

Medieval safari

Leaving grad school, I vaguely knew that the brave new world of Nine-to-Five Desk Job I was stepping into would introduce changes into the lifestyle of the beautiful and fabulous that I had grown accustomed to, but, as everything goes in life, it doesn't quite hit you until you're in it. WHAT DO YOU MEAN I CAN'T SPEND THE AFTERNOON RESEARCHING?* Several weeks of not reading recently made me realize that intellectual stimulus is forever tied to my mental health, and so out came those life-long, marketable skills liberal arts graduates always gush about: reading scheduling and annotating. Somehow, things got out of control and I find myself in the middle of a medieval literary extravaganza. Even so, I've still felt out of sorts lately, which I'm diagnosing as a major case of writer's block; I thought I'd force some writing out of me by talking about what I've been reading.

After steady urging by my peers, I read Craig Carter's Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition, which is based on the assumption that the Enlightenment has undermined the foundation of Western culture by attacking its hermeneutic of reading, specifically in a biblical context. Carter had me at: "This book tries to restore the delicate balance between biblical exegesis, trinitarian dogma, and theological metaphysics that was upset by the heretical, one-sided, narrow-minded movement that is misnamed 'the Enlightenment'" (26). I've been saying for years that the Enlightenment ended Western Civilization, so I find it extremely satisfying to have this prejudice validated in an academic, peer-reviewed text. ANYWAY, Carter devotes the rest of his book to advocating a return to a medieval ethic of interpreting Scripture, specifically its use of allegory in tandem with literal readings of the texts. Much of this would be familiar to old-school English students, who are taught to approach reading as Keats did, as something that is self-reflexive and that necessarily changes those who encounter it. I'm still not entirely sure about how much I track Carter on his (reductionist?) analysis of Nominalism as the ultimate culprit (though as a Realist I have no sympathy for the movement), but it gives much to think about. I was also particularly interested in the juxtaposition of his extensive use of Tolkien and Lewis and his deflationary discussion of the idea of the "Christian Myth" - I think there are a lot of potential nuances waiting to be teased out here. All in all a book I thoroughly enjoyed reading.

I just finished Ian Levy's Introducing Medieval Biblical Interpretation. We share an alma mater, which thus gave him instant credibility with me. As you might suspect from the title, he takes a different approach from Carter by producing a survey of medieval writers, rather than pursuing a thesis-driven argument. While I would have enjoyed the latter more, I appreciated the chance to read this as a companion text to Carter, as it gave me the chance to see what the literary milieu Carter describes was doing on the ground. In the recurring game I play with myself, if I were a professor, I would definitely assign the two texts together.

Other books I’ve gotten through lately have been Madeleine Miller’s Circe, Rosaria Butterfield’s The Gospel Comes with a House Key, and The Church’s Book of Comfort (a collection of essays on the Heidelberg Catechism put out by Reformation Heritage), and I’m currently reading Trueman’s Grace Alone. However, to keep these medieval vibes going, I’ve got my eye on Chris Armstrong’s Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians and Christine de Pisan’s The Treasure of the City of Ladies. I still owe the blog my thoughts on Marie de France, because, months later, she is still a legend in my mind. But I’ll have to schedule all this writing in.

Other books I’ve gotten through lately have been Madeleine Miller’s Circe, Rosaria Butterfield’s The Gospel Comes with a House Key, and The Church’s Book of Comfort (a collection of essays on the Heidelberg Catechism put out by Reformation Heritage), and I’m currently reading Trueman’s Grace Alone. However, to keep these medieval vibes going, I’ve got my eye on Chris Armstrong’s Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians and Christine de Pisan’s The Treasure of the City of Ladies. I still owe the blog my thoughts on Marie de France, because, months later, she is still a legend in my mind. But I’ll have to schedule all this writing in.

-----

*you know, chasing that dopamine high we all get when we encounter an out-of-print lyric text by Hercules Collins

Friday, August 17, 2018

Memento mori

Let’s talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs,Make dust our paper, and with rainy eyesWrite sorrow on the bosom of the earth.Let’s choose executors and talk of wills.And yet not so, for what can we bequeathSave our deposèd bodies to the ground?Our lands, our lives, and all are Bolingbroke’s,And nothing can we call our own but deathAnd that small model of the barren earthWhich serves as paste and cover to our bones.For God’s sake, let us sit upon the groundAnd tell sad stories of the death of kings—How some have been deposed, some slain in war,Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed,Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed,All murdered. For within the hollow crownThat rounds the mortal temples of a kingKeeps Death his court, and there the antic sits,Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp,Allowing him a breath, a little scene,To monarchize, be feared, and kill with looks,Infusing him with self and vain conceit,As if this flesh which walls about our lifeWere brass impregnable; and humored thus,Comes at the last and with a little pinBores through his castle wall, and farewell, king!Cover your heads, and mock not flesh and bloodWith solemn reverence. Throw away respect,Tradition, form, and ceremonious duty,For you have but mistook me all this while.I live with bread like you, feel want,Taste grief, need friends. Subjected thus,How can you say to me I am a king?

(Richard II III.ii.150-182)

I didn’t appreciate Richard II in quite the way that Shakespeare intended it until I encountered corruption myself. Richard II was a far cry from the ruthlessness of Richard III, but his weakness is just as reprehensible as the latter’s criminality. I am naturally cautious, and I have learned that timidity can wield just as much injustice as tyranny. Sin overturns kingdoms with disturbing rapidity.

Monday, April 16, 2018

Sweet peace

The doubt which ye misdeeme, fayre loue, is vaine

That fondly feare to loose your liberty,

when loosing one, two liberties ye gayne,

and make him bond that bondage earst dyd fly.

Sweet be the bands, the which true loue doth tye,

without constraynt or dread of any ill:

the gentle birde feeles no captiuity

within her cage, but singes and feeds her fill.

There pride dare not approch, nor discord spill

the league twixt them, that loyal loue hath bound:

but simple truth and mutuall good will,

seekes with sweet peace to salue each others wound

There fayth doth fearlesse dwell in brasen towre,

and spotlesse pleasure builds her sacred bowre.

(Spenser, Amoretti, #65)

Wednesday, April 4, 2018

In my end is my beginning

I'm in a seminar on T.S. Eliot this semester, and lately we've been reading his Four Quartets. The final stanzas of "East Coker" struck me as particularly beautiful. I've often encountered poetic interventions in life, when a piece crosses my path precisely when I need it most; it's both poignant and cathartic. This was one of those.

Home is where one starts from. As we grow older

The world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated

Of dead and living. Not the intense moment

Isolated, with no before and after,

But a lifetime burning in every moment

And not the lifetime of one man only

But of old stones that cannot be deciphered.

There is a time for the evening under starlight,

A time for the evening under lamplight

(The evening with the photograph album).

Love is most nearly itself

When here and now cease to matter.

Old men ought to be explorers

Here and there does not matter

We must be still and still moving

Into another intensity

For a further union, a deeper communion

Through the dark cold and empty desolation,

The wave cry, the wind cry, the vast waters

Of the petrel and the porpoise. In my end is my beginning.

My life is not my own; I do not reserve the right to tell God how I serve Him. Peace comes from obedience.

Friday, March 23, 2018

A concession

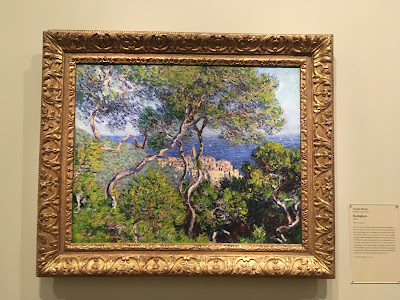

Obligatory Impressionist painting accompanying Victorian novel

"We all of us, grave or light, get our thoughts entangled in metaphors, and act fatally on the strength of them."

George Eliot, Middlemarch

I recently sat for my MA exam, and studying for this meant ingesting as much of a 36-author reading list as possible. The idea is to produce graduates who are generalists in Anglophone literature, so the list included everyone from Marie de France (who is a PARTAY and deserves a post of her own) to Salman Rushdie.* One of the authors I had to meet for the first time was George Eliot. Going into it, I was pretty stoked to read Middlemarch, because I had heard so much about it from authors I respect, who highlighted its discussion of female agency and intellectualism. Unfortunately, my longstanding struggle with literary Realism was not about to dissipate, and Middlemarch required some of the most stamina I have ever needed in order to finish a book. I couldn't deal with all....that....detail. The entire time reading, I couldn't help thinking that what Eliot would take 150 pages to write, Austen could say in one paragraph. Oh well. (Also Dorothea Brooke is one of the most annoying characters I have encountered. So much for cool, intellectual heroines.)

ANYWAY, I didn't intend for this post to be a rant about Victorian novels. Instead, the above quote turned itself over and over in my head as I read Middlemarch, and I think it's a perfect summary of the novel as a whole. Hypothetical Reader, do not bother trying to tackle all 800 pages of that book; this quote is all you need to know. #lifehacks However, beyond the quote's nature as a key to reading the novel, I really liked it for its own merit as well. Eliot was spot on in diagnosing why we make so many of the stupid decisions we later (or instantly) regret. I was going to try writing a whole blog post expanding on this quote, but the more I try, the more I realize that it really just stands on its own. There is a tangible power to metaphor, and having the self-awareness to recognize how this plays on your perception of the world is incredibly valuable.

Even though I hated almost my entire experience of reading Middlemarch, I consider it worth it for just that one insight.

----------

* No, I did not read all 36. This is grad school, remember? The true learning objective is being able to correctly guess which items on an unreasonable reading list are the ones you're supposed to know. Pamela did not make the cut.**

** I would like to add that said exam, in an administrative decision undoubtedly sadistic, took place DURING SPRING BREAK.***

*** All professors seemed to have forgotten the imminence of said exam and assigned us EXTRA homework in the weeks leading up to it. Ok, rant over, I promise.

Wednesday, March 21, 2018

In which I orate

“According to Scripture...marriage is an exalted state. But it is not the only God-pleasing state in which we can live. While the church does well to affirm marriage and childbearing, it often does a disservice to many of its members by marginalizing the nonmarried and the childless. This can happen in various ways. For example, it can happen when churches advertise themselves as being family friendly or as supporting family values, even when many of their members do not have a family, at least not a spouse or children. It can happen when churches treat unmarried adults simply as those who are not yet married, as if their lives are in a holding pattern until marriage brings meaning to them. It can happen when Christians segregate their social lives, as if the people who are married with children should primarily associate with each other and unmarried people with each other (and, when they do mingle, by people talking incessantly about their children as if those without children find such conversations just as fascinating as they do). It can happen when Christians raise girls as if being a wife and mother is the only worthy goal to pursue in life, such that those who do not marry and have children feel that they have somehow failed and are unprepared to find valuable things to do.”

(Bioethics and the Christian Life, p. 100)

I’ve long been convinced that this is one of the ways the Church today often falls into profound self-destruction. Every one of VanDrunen’s examples has been deeply relatable for me, not only in the local church but the culture of Christianity at large. Touting ourselves as “family friendly” does at least as much harm as the good it believes itself to do, because doing so marginalizes the very demographic that Scripture itself claims is most physically able to serve the church. Furthermore, identifying ourselves primarily by “family values” is indicative of an underlying social gospel - “moral” conduct is now more important than purity of worship or theological integrity. It’s impossible to get the “practical” aspects of Christian living right if we don’t understand them as a product of God-glorifying doxology and doctrine first; failure to do so leads to legalism and, often, abuse.

The best examples of church life I have witnessed were cases in which the church’s theology and worship flowed into proper relationships between members of the congregation; single people in particular were valued for their own sake. They were not treated as inconvenient problems to be solved, second-class adults waiting to finally “grow up,” and they were neither patronized nor exploited. They were seen as individuals who had something to offer to the rest, and were encouraged to maximize these abilities. The fruit of such an attitude played out in the singles’ active involvement in church life. The church needed them. I can’t help but think how much more our churches could flourish if they shared this attitude.

Living in the church for 24 years, I have witnessed how a change in an individual's relationship status can launch - overnight - a flurry of invitations and overtures of friendship which had previously never been offered. This kind of thing can't go on. If there is only one practical takeaway from this post, let it be this: Treat singles as equals (because that's exactly what they are before God).

Thursday, March 8, 2018

Atta boy Sidney

Since, then, poetry is of all human learnings the most ancient and of most fatherly antiquity, as from whence other learnings have taken their beginnings; since it is so universal that no learned nation doth despise it, nor barbarous nation is without it; since both Roman and Greek gave divine names unto it, the one of “prophesying,” the other of “making,” and that indeed that name of “making” is fit for him, considering that whereas other arts retain themselves within their subjects, and receive, as it were, their being from it, the poet only bringeth his own stuff, and doth not learn a conceit out of a matter, but maketh matter for a conceit; since neither his description nor his end containeth any evil, the thing described cannot be evil; since his effects be so good as to teach goodness, and delight the learners of it; since therein—namely in moral doctrine, the chief of all knowledges—he doth not only far pass the historian, but for instructing is well nigh comparable to the philosopher, and for moving leaveth him behind him; since the Holy Scripture, wherein there is no uncleanness, hath whole parts in it poetical, and that even our Saviour Christ vouchsafed to use the flowers of it; since all his kinds are not only in their united forms, but in their several dissections fully commendable; I think, and think I think rightly, the laurel crown appointed for triumphant captains doth worthily, of all other learnings, honor the poet’s triumph.

(The Defense of Poesy, The Major Works, Oxford, p. 232)

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

2018

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

(Dylan Thomas, 1951)

Technically, this poem is Dylan Thomas's meditation upon the aging of his father and fight against imminent death. It's consistently been lurking in the back of my mind for the past few months, and I think there is more to its call to arms than simply resistance to physical mortality. I read Thomas's "rage" not as an act of violence or wrath, but rather as a nuanced manifestation of fierce, principled persistence. It brings to mind the literary types of the tragic and pathetic. The latter is passive, too consumed with the pathos of the moment to make any more attempt at resistance in the face of defeat. The tragic, however, dies fighting. In a spiritual sense, it is connected with Watson's imagery of Heaven being taken by storm. Leaving this here as a reminder that my faith, my church, my hope are all things I can never take for granted or give up in despair; through God's grace, they are things worth fighting for.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)